As Cannes Lions 2015 begins, my thoughts on some other needed awards for creativity in advertising. To read, please visit my new website at http://jdavidslocum.com .

Showing posts with label Cannes Lions. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Cannes Lions. Show all posts

Saturday, June 20, 2015

Sunday, July 27, 2014

Building New Strategies with Lessons of the Past

At last month’s Cannes Lions festival, I had the privilege

of participating in a session with advertising legend Chuck Porter on “building

new strategies for creative excellence.”

The session was organized by the Berlin School of Creative Leadership around

the contrast between strategic insights drawn from the successful creative work

of his agency, Crispin Porter + Bogusky, and more orthodox strategic approaches

associated with Harvard Business School Professor Michael E. Porter (no

relation). In preparation, my Berlin

School colleague, Professor Paul Verdin, and I had drafted a White Paper on the

topic.

The session and paper yielded several conclusions about new

priorities for building strategy for creative excellence. For example, while acknowledging the greater need

for flexibility and speed in decision-making today, we identified the persisting

importance of making adaptive commitments to brand values and strategic

priorities. Likewise, we identified

other crucial principles: serving communities of participation, building trust

through storytelling, and finally recognizing accumulative value creation

rather than pursuing competitive advantage for strategic success. Overall, we proposed a fundamental shift from

the traditional, largely adversarial orientation focused on competitors to an

emphasis on value creation through the engagement of customers.

In doing so, the White Paper picked up on several currents

of thought about the evolution of strategy.

Customer-centricity, involving better understanding and engagement of

customers as well as enhancing capabilities for serving customers, is one such

stream. Another is the transformation of

traditional value chain and scale economies by digital technologies and an

information economy whose creation, distribution, and transaction costs have an

entirely different structure. Perhaps

best-known, to use the title of Rita Gunther McGrath’s 2013 book, is “the end

of competitive advantage.” Rather than

achieving a long-term, stable and sustainable market position in a well-defined

industry, following Michael Porter, the new world of strategy is marked by

developing a portfolio of transient advantages able to capture shifting

“connections between customers and solutions.”

At same time as the Cannes festival, another debate around

innovation and disruption began roiling.

Jill Lepore, a professor of history at Harvard (in the Faculty of Arts

and Science, not Business School), published a withering piece on the

contemporary “gospel of innovation” in The New Yorker. “The Disruption Machine” took on the

prevailing model of disruptive innovation associated with Clayton Christensen,

another Harvard Business School faculty member.

His theory contends that while an incumbent firm seeks to maintain its market

advantage through sustaining, or incremental, technological innovations, it is

often overtaken by new entrants whose disruptive innovations, typically offered

at lower-cost and with lower-performing technologies, end up remaking the

market and leading to the failure of the incumbent firm. Lepore alleged the theory, which she

extracted primarily from Christensen’s groundbreaking 1997 The Innovator’s

Dilemma, mistakenly explained the emergence of new technologies and the dynamics

of firms. In doing so, she also

personalized the critique by questioning the integrity of his research and his

claims about the theory’s ability to predict market failures. In a Bloomberg BusinessWeek

interview, Christensen responded briefly and quizzically both about the

personal nature of the attack and the lack of actual difference in their

questioning of innovation.

Much commentary and side-taking has ensued. Many pieces noted how “disruption,” in

particular, had become an overused shorthand for innovation-driven (some would

say, -fixated) entrepreneurs and businesses.

On Vox.com, for instance, Timothy B. Lee’s post was tellingly titled,

“Disruption is a dumb buzzword. It’s

also an important concept.” Kevin Roose similarly wrote on nymag.com that,

“for actual disruption to work best,‘disruption’ has got to go.” Some comments took on the larger state of innovation in

both business and management studies. In

the Financial Times, Andrew Hill thus made the case for a more measured

use of the theory of disruption, citing its relevance to analyzing corporate

failures like Kodak and Blackberry.

While Christensen has understandably been at the heart of many

of these discussions, Michael Porter’s place has also been important. On Forbes.com, Stephen Denning wrote

that Lepore had been “the assistant to the assistant of Porter” and he then

cast her attack in terms of the conflicting views of Porter and Christensen. Specifically, this meant distinguishing the

strategic goals of maximizing shareholder value and creating and maintaining

customers. The recent imbroglio around

disruption is a “symptom,” in Denning’s word, of a more far-reaching debate

around core assumptions of contemporary management and business.

In fact, among the most important lessons of the Lepore-Christensen

exchange seem precisely the value of reflecting on and wrestling with one’s own

guiding principles and assumptions in business leadership. That lesson was also a basis of the Porter

vs. Porter White Paper and Cannes session.

Such questioning can include:

1. Language

Too often, as with “disruption,” we use or overuse language

without fuller explanation or understanding.

Sometimes context is lacking. For

those in creative and marketing communications, for instance, Jean-Marie Dru,

now the Chairman of the TBWA Worldwide advertising agency, developed the

distinct concept and specific creative methodology of “disruption” at the same

time as Christensen in the mid-1990s. More generally, as I wrote in a recent post,

we don’t take adequate care in our everyday usage of key words like innovation and

creativity to ensure clear and effective communication of their meaning in

given situations.

2. Assumptions and Contexts

If the language around disruption or innovation would benefit

from greater care and precision of usage, the assumptions underpinning that

language can likewise have greater impact when more fully understood. This is not to suggest, of course, that any

discussion of innovation should revert to exploring the finer points of

Christensen’s (or Porter’s) research. It

is, however, to posit the value of stepping back and assessing the larger ideas

behind, or wider implications of, specific potential decisions, actions or

strategies. Some of the best

commentaries on Lepore and Christensen, like John Hagel’s, are illuminating exactly

because they analyze seemingly familiar ideas more acutely and pose bigger

questions.

3. Beyond Prediction

One of Lepore’s major critiques in “The Disruption Machine”

is how poorly Christensen’s model predicts business success or failure due to

disruptive innovation. Similarly, in the

Cannes session, Chuck Porter observed how our White Paper about his agency’s

creative work amounted to “backfilling” explanations for earlier strategic and

creative work that may not be practically useful going forward. Any prediction or forecasting for an

increasingly uncertain future is obviously challenging. Yet predicting the future is not the only

standard or purpose for analyzing and modeling the past. Even more, as Lepore herself allows (in

quoting a recent New York Times report on innovation), “disruption is a

predictable pattern across many industries” – patterns being a matter of deeper

understanding and far different from concrete predictions about future performance

at specific firms.

4. Models and

Theories – and Learning

The distinction is essential. As an educator who uses historical cases and models,

my priority is often to connect particular examples to wider patterns. However, the purpose in doing so is not the

connections themselves but to help build individuals’ capacities for effective

analysis and action. Those capacities

are enabled by learning multiple examples and experiences, models and patterns,

and developing the discernment and agility to use them, as appropriate, to

make sense of different situations and contexts. Models and theories, like that of disruptive

innovation, are always only potential means for conducting analyses. Rather than ends in themselves, we should look

to them to help us improve our thinking, sharpen frames of reference, and

ultimately serve as aids to better understanding, decisions, and

problem-solving.

Friday, June 20, 2014

Building New Strategies for Creative Excellence: Michael Porter vs. Chuck Porter

On Thursday evening, June 19, I had the privilege of

presenting ideas for 'building new strategies for creative excellence' at the Cannes

Lions International Festival of Creativity. The session grew out of a

White Paper with the same title co-authored with my Berlin School of Creative

Leadership colleague, Professor Paul Verdin. Guiding both session and paper were a series of contrasts drawn between the strategic thinking of Harvard Professor Michael Porter and the strategy Paul and I identified in the words and work of advertising legend Chuck Porter. (The full paper is

downloadable here.)

The Executive Summary reads:

Strategy is changing amidst volatile markets, disruptive

technologies, and transformed customer and public relationships. Contrasting

some of the major tenets of traditional strategic thinking, an analysis of the

work and words of Chuck Porter enables the mapping of several key principles of

a new strategy of creative excellence. These include 1) forming an

adaptive commitment to strategic intent and ongoing public engagement, 2)

fostering communities of participation as part of generating a wider cultural

conversation of creative work, 3) building trust through imaginative, often

offbeat and interactive storytelling, and 4) moving beyond competition to

highlight the value emerging through creative breakthroughs or

community-building.

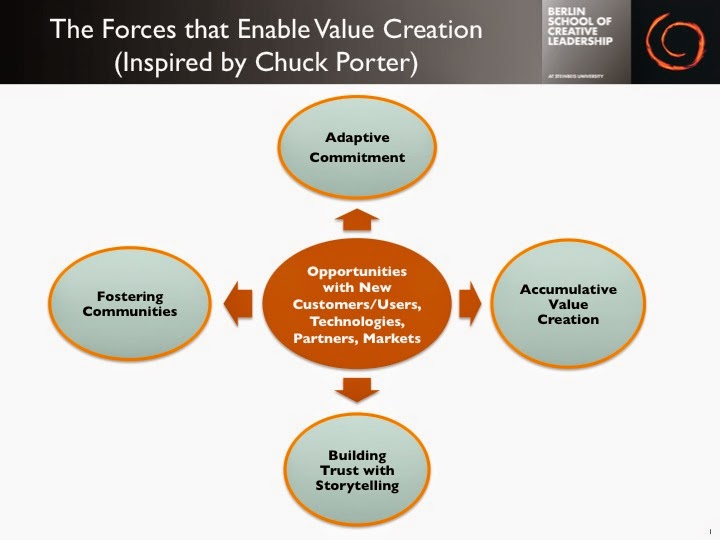

The following images give a further sense of the contrast we draw between the 'Five Forces' model of industry competition that shape firm strategy of Michael Porter and the emergent Forces that enable value creation we associate with Chuck Porter.

Saturday, June 14, 2014

Cannes Lions as Global Creative Leadership Classroom

The Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity held

each June is the world’s leading celebration of brand communications and

creativity. The official programme of

the week-long festival combines a dizzying array of industry and agency

showcases, formal seminars, lectures, workshops, teaching academies, and award

shows. Arguably even more happens

unofficially, with agency and holding companies gathering their global talent

and leadership, often with clients, in meetings and parties, and with informal business

meetings and social gatherings occurring around the clock.

For each of the last five years, the Berlin School ofCreative Leadership has partnered with Cannes Lions to offer the premiere

educational programme among the many held at the festival. The Cannes Creative Leaders Programme (CCLP) begins

with six intensive days of leadership training in Berlin followed by six days

of the festival curation and closed-door sessions with industry leaders in

Cannes. While individual faculty,

industry speakers and sessions provide many specific insights to programme

participants, CCLP also emphasizes how more generally to learn from the

festival itself – from Cannes as a model classroom for creative excellence. The result is a fresh approach to sustaining

creative and intellectual stimulation both within individual businesses and at

other idea and creativity festivals.

Here are a handful of the touchstones we urge participants

to adopt in making the most from the festival:

·

Relevance

Why should I care about what’s said

or shown on the stage at Cannes when we are pursuing creative excellence? It’s a large question but an essential one:

beyond the hype and personality cults and justifiable admiration for strong imaginative

work, what is relevant to my own creative leadership and why? Is a brand, client or consumer problem being defined

and an original solution being plotted, one or both of which may be relevant to

my own situation (either now or in the foreseeable future)? Direct relevance and applicability are not

the only tests of value, of course, but particularly in sessions featuring

high-profile individuals or agencies, we do well by asking what concretely are

the ideas or insights being shared and how are they relevant to our own

work. Too often, on big stages in Cannes

and elsewhere (from other live events like MIPTV for television professionals to

online offerings like TED), we partake in what I call “popcorn creative

thinking” – easy and even enjoyable to consume in the moment but failing to

provide any real nourishment or impact. The more we question relevance and value, the

more sharply we gather knowledge and insights from others that can help to make

us better leaders.

·

Inspiration

Part of what animates Cannes is a

core tenet of creative leadership and all creative work: inspiration. We’re inspired by the examples of new

standards of work that move the industry forward and even improve society, the

innovative solutions to business and human problems, and the perspectives of

leading voices and thinkers. Inspiration

doesn’t always readily pass the relevance test, but it is vital to advancing

creative excellence. The challenge is to

know how to take the inspiration of a Cannes session or speaker (or, again, those

at any number of other events) back home to enrich our own work. Sometimes the answer is as simple as

reflecting on what kind of inspiration we’re experiencing. In its 2012 CEO survey, IBM looked closely at

what constituted inspirational leadership and revealed five major

characteristics: creating a compelling vision, driving stretch goals, hewing to

shared principles, exercising enthusiasm, and guiding with expertise. By asking that additional question – how specifically are we being inspired? – we

increase the likelihood of taking away practical knowledge of how to sustain

the inspiration of the moment and use it to lead others.

·

Idea Events

Part of the attraction, even magic,

of Cannes Lions is that it happens only once a year. Thousands gather from around the world and

produce a singular, energetic mass of industry voices, experience and

successful work. The festival

consequently becomes what anthropologists call a “tournament of values,” a site

where the priorities of a community, here of global creative communication

professionals, determines its leading values, standards and priorities. Tracking closely which values – or ideas,

debates, challenges, and kinds of work – are highlighted and celebrated helps

further our understanding of the shape and future of the industry. Viewed this way as a hothouse of industry ideas,

however, Cannes Lions also becomes a model for us as individual leaders to

stimulate thinking and engage diverse ideas more consistently. Put in more practical terms, how do we as

creative leaders construct similar opportunities for our teams or businesses to

learn from and be inspired by multiple voices and engage in industry-defining

debates and conversations? Many

organizations, large and small, from BBDO’s Digital Lab to Pixar University,

have institutionalized such continuing engagement with diverse and innovative

ideas. The question remains for us, how

are we doing so in ours?

·

Creativity

Voyeurism

Common to testing relevance,

sustaining inspiration, and continuing engagement with diverse ideas is the

challenge of actively taking home the experiences and insights of Cannes and

making them a part of our own creative leadership practice. Again, not all lessons or experiences of

Cannes Lions or other events can or should be immediately applicable (some of

what happens in Cannes should indeed stay in Cannes…). But too often, the big names, the

trend-setting work, and the fresh ideas – and a kind of romance with creativity

they often come to represent – can turn us into passive viewers and admirers. As an educator of professionals and

executives, this tendency casts light on a special imperative for me in any

setting in which I work: what will you do with what you’ve learned? For creatives, the added burden of what I

call “creativity voyeurism” can dull our capacity to embrace and transfer the

rich diversity of ideas we experience.

Put simply, often the greatest challenge of participating in Cannes

Lions or any idea festival is to act concretely and locally after the event is

over.

·

Making

the Story Your Own

We have the good fortune to be

living in (and hopefully contributing to) a golden age of creativity and

innovation in business. From reading Fast Company, Inc. and Entrepreneur to

following our favorite TED-talks and video blogs to attending Cannes Lions and

SXSW, we are awash in tales of creative leadership, bleeding-edge practices,

and innovative possibility. Yet the

voyeurism I’ve mentioned, while allowing us to be cocktail-party conversant in

what our creative heroes are doing, can easily leave us doing little if any

comparable work ourselves. One of the

exercises we do in CCLP is to respond to sessions, speakers or experiences at

Cannes Lions by creating our own individual stories about them. They may be stories we would tell our bosses,

our clients, our friends or loved ones and they may speak to the opportunity,

awe or even irrelevance of the ideas or experiences. But what’s crucial is that the stories of

creativity become ours. In the crucible of storymaking, we at least

begin to transfer the creative leadership, learning and experience of others to

ourselves. In that way, we take a

critical step toward making real for us the

extraordinary ideas, insights, excitement, and possibilities of Cannes.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)