At last month’s Cannes Lions festival, I had the privilege

of participating in a session with advertising legend Chuck Porter on “building

new strategies for creative excellence.”

The session was organized by the Berlin School of Creative Leadership around

the contrast between strategic insights drawn from the successful creative work

of his agency, Crispin Porter + Bogusky, and more orthodox strategic approaches

associated with Harvard Business School Professor Michael E. Porter (no

relation). In preparation, my Berlin

School colleague, Professor Paul Verdin, and I had drafted a White Paper on the

topic.

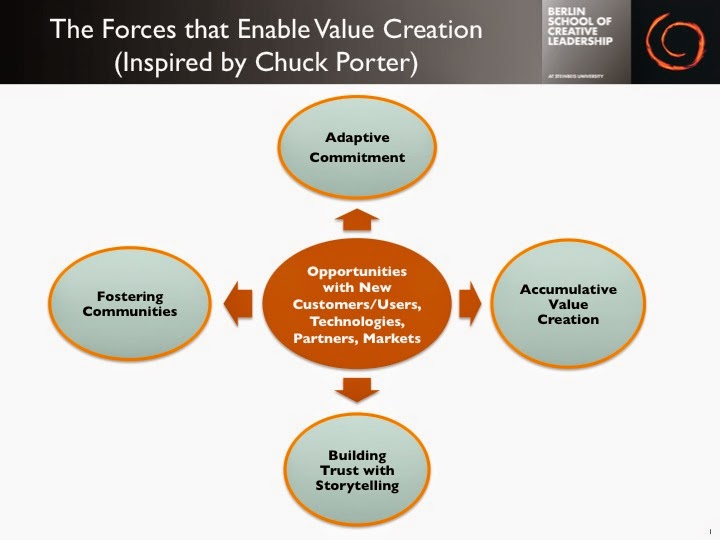

The session and paper yielded several conclusions about new

priorities for building strategy for creative excellence. For example, while acknowledging the greater need

for flexibility and speed in decision-making today, we identified the persisting

importance of making adaptive commitments to brand values and strategic

priorities. Likewise, we identified

other crucial principles: serving communities of participation, building trust

through storytelling, and finally recognizing accumulative value creation

rather than pursuing competitive advantage for strategic success. Overall, we proposed a fundamental shift from

the traditional, largely adversarial orientation focused on competitors to an

emphasis on value creation through the engagement of customers.

In doing so, the White Paper picked up on several currents

of thought about the evolution of strategy.

Customer-centricity, involving better understanding and engagement of

customers as well as enhancing capabilities for serving customers, is one such

stream. Another is the transformation of

traditional value chain and scale economies by digital technologies and an

information economy whose creation, distribution, and transaction costs have an

entirely different structure. Perhaps

best-known, to use the title of Rita Gunther McGrath’s 2013 book, is “the end

of competitive advantage.” Rather than

achieving a long-term, stable and sustainable market position in a well-defined

industry, following Michael Porter, the new world of strategy is marked by

developing a portfolio of transient advantages able to capture shifting

“connections between customers and solutions.”

At same time as the Cannes festival, another debate around

innovation and disruption began roiling.

Jill Lepore, a professor of history at Harvard (in the Faculty of Arts

and Science, not Business School), published a withering piece on the

contemporary “gospel of innovation” in The New Yorker. “The Disruption Machine” took on the

prevailing model of disruptive innovation associated with Clayton Christensen,

another Harvard Business School faculty member.

His theory contends that while an incumbent firm seeks to maintain its market

advantage through sustaining, or incremental, technological innovations, it is

often overtaken by new entrants whose disruptive innovations, typically offered

at lower-cost and with lower-performing technologies, end up remaking the

market and leading to the failure of the incumbent firm. Lepore alleged the theory, which she

extracted primarily from Christensen’s groundbreaking 1997 The Innovator’s

Dilemma, mistakenly explained the emergence of new technologies and the dynamics

of firms. In doing so, she also

personalized the critique by questioning the integrity of his research and his

claims about the theory’s ability to predict market failures. In a Bloomberg BusinessWeek

interview, Christensen responded briefly and quizzically both about the

personal nature of the attack and the lack of actual difference in their

questioning of innovation.

Much commentary and side-taking has ensued. Many pieces noted how “disruption,” in

particular, had become an overused shorthand for innovation-driven (some would

say, -fixated) entrepreneurs and businesses.

On Vox.com, for instance, Timothy B. Lee’s post was tellingly titled,

“Disruption is a dumb buzzword. It’s

also an important concept.” Kevin Roose similarly wrote on nymag.com that,

“for actual disruption to work best,‘disruption’ has got to go.” Some comments took on the larger state of innovation in

both business and management studies. In

the Financial Times, Andrew Hill thus made the case for a more measured

use of the theory of disruption, citing its relevance to analyzing corporate

failures like Kodak and Blackberry.

While Christensen has understandably been at the heart of many

of these discussions, Michael Porter’s place has also been important. On Forbes.com, Stephen Denning wrote

that Lepore had been “the assistant to the assistant of Porter” and he then

cast her attack in terms of the conflicting views of Porter and Christensen. Specifically, this meant distinguishing the

strategic goals of maximizing shareholder value and creating and maintaining

customers. The recent imbroglio around

disruption is a “symptom,” in Denning’s word, of a more far-reaching debate

around core assumptions of contemporary management and business.

In fact, among the most important lessons of the Lepore-Christensen

exchange seem precisely the value of reflecting on and wrestling with one’s own

guiding principles and assumptions in business leadership. That lesson was also a basis of the Porter

vs. Porter White Paper and Cannes session.

Such questioning can include:

1. Language

Too often, as with “disruption,” we use or overuse language

without fuller explanation or understanding.

Sometimes context is lacking. For

those in creative and marketing communications, for instance, Jean-Marie Dru,

now the Chairman of the TBWA Worldwide advertising agency, developed the

distinct concept and specific creative methodology of “disruption” at the same

time as Christensen in the mid-1990s. More generally, as I wrote in a recent post,

we don’t take adequate care in our everyday usage of key words like innovation and

creativity to ensure clear and effective communication of their meaning in

given situations.

2. Assumptions and Contexts

If the language around disruption or innovation would benefit

from greater care and precision of usage, the assumptions underpinning that

language can likewise have greater impact when more fully understood. This is not to suggest, of course, that any

discussion of innovation should revert to exploring the finer points of

Christensen’s (or Porter’s) research. It

is, however, to posit the value of stepping back and assessing the larger ideas

behind, or wider implications of, specific potential decisions, actions or

strategies. Some of the best

commentaries on Lepore and Christensen, like John Hagel’s, are illuminating exactly

because they analyze seemingly familiar ideas more acutely and pose bigger

questions.

3. Beyond Prediction

One of Lepore’s major critiques in “The Disruption Machine”

is how poorly Christensen’s model predicts business success or failure due to

disruptive innovation. Similarly, in the

Cannes session, Chuck Porter observed how our White Paper about his agency’s

creative work amounted to “backfilling” explanations for earlier strategic and

creative work that may not be practically useful going forward. Any prediction or forecasting for an

increasingly uncertain future is obviously challenging. Yet predicting the future is not the only

standard or purpose for analyzing and modeling the past. Even more, as Lepore herself allows (in

quoting a recent New York Times report on innovation), “disruption is a

predictable pattern across many industries” – patterns being a matter of deeper

understanding and far different from concrete predictions about future performance

at specific firms.

4. Models and

Theories – and Learning

The distinction is essential. As an educator who uses historical cases and models,

my priority is often to connect particular examples to wider patterns. However, the purpose in doing so is not the

connections themselves but to help build individuals’ capacities for effective

analysis and action. Those capacities

are enabled by learning multiple examples and experiences, models and patterns,

and developing the discernment and agility to use them, as appropriate, to

make sense of different situations and contexts. Models and theories, like that of disruptive

innovation, are always only potential means for conducting analyses. Rather than ends in themselves, we should look

to them to help us improve our thinking, sharpen frames of reference, and

ultimately serve as aids to better understanding, decisions, and

problem-solving.